Click to download document

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the generous leaders from the community services and peak bodies who shared their knowledge, insights, and experience for this project. This report is an output of the Australian Community Sector Study 2021 research project, commissioned by the Australian Council of Social Service and the Councils of Social Service in partnership with Bendigo Bank, Australia’s better big bank. Previous reports from the Australian Community Sector Survey can be found at https://www.acoss.org.au/australian-community-sector-survey/

ISSN: 1326 7124

ISBN: 978 0 85871 110 5

© Australian Council of Social Service 2022

This report was written by Dr Natasha Cortis and Dr Megan Blaxland from the Social Policy Research Centre at UNSW Sydney.

This report should be referenced or cited as follows: Cortis N and Blaxland, M (2022) Carrying the costs of the crisis: Australia’s community sector through the Delta outbreak. Sydney: ACOSS

This publication is copyright. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Enquiries should be directed to the Publications Officer, Australian Council of Social Service. Copies are available from the address above.

Key Findings

- COVID-19 has revealed the impacts of chronic under-investment in the community sector. Organisations whose financial outlook is worst are more likely to be those who are reliant on the Federal Government for their main income stream.

- Only 20% of community sector organisations said that their main funding source covers the full costs of service delivery; and only 14% said that indexation arrangements for their main funding source was adequate.

- While 5-year contracts are beneficial for service delivery, planning and staff retention, they are far from universal, with only 40% of respondents stating that their organisation has at least one contract with government of 5 years or more.

- 5-year contracts are less common among organisations whose main income source is the Federal Government.

- Just over half of all organisations surveyed received only 2-8 weeks’ notice of renewal of government funding contracts, making it impossible to plan with certainty.

- Only 5% of organisations reported at least 6-months’ notice of contract renewal.

- The majority of respondent organisations either have contracts that preclude engagement in systemic advocacy (27%) or are concerned about the possible ramifications of doing so (38%).

- A majority of employees are working extra unpaid hours, on average 15% of total hours worked (25% for CEOs and 10% for frontline workers)

- The uncertain funding environment constrains job security and employee confidence for their immediate future.

> 73% of fixed-term employees’ contracts are linked to the funding cycle;

> The majority of workers planning to leave are doing so due to problems such as insufficient paid hours of work and lack of permanent work due to funding uncertainty. - Respondent organisations highlighted the hugely beneficial impacts of the introduction of the Coronavirus Supplement for the people using their services: Doubling the jobless payment in 2020 was the number one factor in improving family functioning for the families I was working with and the disturbing impacts of its removal: …real hardship was the result. This also caused mental health issues and increased sense of betrayal and dismissal by government.

Part 1

Executive Summary

This report explores the experiences of , captured for the Australian Community Sector Survey (ACSS) during September 2021.[1] Participants shared their perspectives on working in the community sector through 2021, including during the COVID-19 Delta outbreak. Questions covered service delivery, workforce, funding, and contractual arrangements.

Results show the Australia’s community sector responded to the prolonged crisis with determination, resilience, innovation, and extraordinary industriousness. Participants provided multiple accounts of the ways organisations swiftly adapted service models to sustain appropriate support for people experiencing disadvantage, poverty, and hardship, and to help communities navigate health, economic and social disruption.

However, the community sector also faced significant challenges in 2021, as governments adopted more passive approaches to managing the crisis, withdrawing financial supports before the crisis subsided, and shifting responsibility onto individuals, families, and communities. The Federal Government’s withdrawal of the Coronavirus Supplement in April 2021 reduced JobSeeker payment levels, despite the demonstrated benefits this essential financial support had for millions of people on low income.[2] The community sector saw the substantial progress made during 2020 in addressing poverty and inequality fall away in 2021.[3] In the absence of adequate government support, community sector workers, organisational leaders and individual service users were left to carry the ongoing costs of the crisis.

Although fortunate in WA to have not experienced extended lockdowns, the lack of housing, decrease in JobSeeker, increased FDV and increased mental health challenges are all notable. (CEO, Housing and homelessness service, WA)

Poverty and hardship remain entrenched

Survey participants were greatly concerned about growing social and economic disadvantage. Housing insecurity, mental health challenges, and difficulties experienced by children and families came through strongly in survey results as persistent problems, in particular for groups with disability and those from non-English speaking backgrounds. These problems were widespread, affecting jurisdictions with lower COVID-19 case numbers as well as the more populous states with higher infections and longer lockdowns.

Funding shortages are acute

The COVID-19 crisis has revealed governments’ chronic under-investment in the community sector. After operating for years with insufficient funds, services have needed to meet rising levels of demand caused by COVID-19.1 Most organisations report that the funding they receive falls well short of what is required, which in turn affects their operations. When asked to rate their organisation’s main funding source:

- Only a minority of leaders reported that funding had adequately supported their organisation to cope with the pandemic: 27% said that funding supported the organisation to develop good models of remote service delivery, and just over a third (35%) felt funding had appropriately supported them to address the emergencies confronting their communities (including COVID and environmental disasters such as fires and floods).Only 20% said it covers the full costs of service delivery.

- Only 17% said it recognises increasing wage costs.

- Only 14% said it properly recognises their overheads.

- Only 14% reported that indexation arrangements for their main funding source are adequate.

A lot of funding opportunities will not cover expenses such as wages, shared expenses such as insurance and rent. (CEO, Legal, advocacy or peak body, NSW)

Even before the Omicron outbreak, many leaders were concerned about the short-term financial position of their organisations. A third of respondents (34%) said their organisation’s financial position had remained about the same, and 29% said their financial position had worsened during 2021, while 31% experienced improvement. A total of 29% of respondents anticipated their finances would worsen in 2022. The financial outlook was poorest among organisations whose main income stream came from the Federal Government.

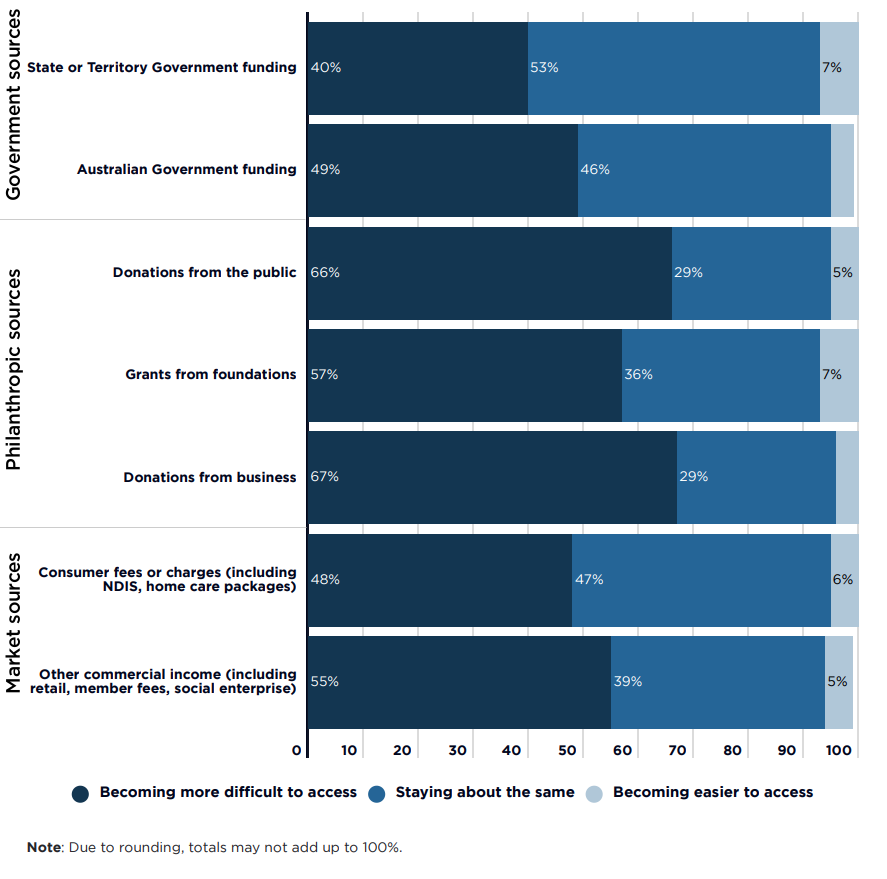

Funding is becoming more difficult to secure

In addition to the acute under-investment in the community sector, many service leaders expressed concern that funding sources are becoming more difficult to secure. Two in three leaders said their organisations are finding it more difficult to source donations from the public and business. Half of respondents said it is becoming more difficult to attract market-based income such as consumer or membership fees. Some have stable government funding, but 45% reported that Australian government funding has become more difficult to access and 40% reported the same problem when sourcing state and territory government funding.

Organisations are left relying on short-term contracts

Contracts are far too short for the sector and affect the retention of staff and the planning of services. Contracts need to be longer in length and give room for more flexibility such as innovation and responding to client need as it arises. (CEO, Health-related service, ACT)

13% of leaders said their organisation’s longest contract was less than 12 months, and a further 10% said their longest contract was less than 2 years.Government resource models have not provided a reasonable level of certainty or predictability. Only a quarter of leaders consider funding timeframes to be long enough (26%). Although five-year contracts are beneficial for service delivery, planning and staff retention, they are far from universal:

- 40% of leaders said their organisation has at least one contract with government of 5 years duration or more.[1]

5-year contracts are more common amongst child, youth, and family services, and least common among organisations focused on ageing, disability, and carer services (21%), financial counselling and support (19%) and migrant and multicultural services (17%). 5-year contracts are also less common among smaller organisations and those for whom the Federal Government is the main income source.

Contract renewal processes remain opaque and problematic

Waiting over 6 months to find out about renewal of program contracts has led to stress and mental health concerns. Many have actively pursued employment elsewhere (Team leader, Child, youth and family service, NT)

Although governments depend on the organisations they contract to deliver complex human services, governments tend to give minimal notice about contract renewals. When asked about the last time a funding contract came up for renewal:

- one in eight leaders (12%) said the organisation received no notice at all as to whether the contract would be renewed, and

- a further 9% received less than 2 weeks’ notice.

Around half (52%) received between 2- and 8-weeks’ notice, giving organisations only a short time to plan ahead, and increasing the risk that staff will lose their jobs with little notice.

Only 5% of leaders said their organisation received at least 6 months’ notice about renewal. This makes it impossible for organisational leaders to plan with certainty.

Contracting arrangements constrain or influence advocacy

Community sector workers and leaders are experts in the impacts of public policy on the community, yet sharing this expertise with government through their advocacy work is still often perceived to jeopardise funding.

- More than a quarter (27%) of leaders said that their organisations have funding contracts that preclude the use of funds for systemic advocacy

- 38% of leaders said they were cautious about engaging in systemic advocacy because of their funding arrangements

- 1 in 5 leaders (19%) said they avoided engaging in systemic advocacy due to concerns about possible repercussions. This was highest among organisations focused on housing and homelessness services, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander services.

We very, very strongly advocate for the service users, families and carers we support, but have definitely felt threatened by some of the language used by our funders. (CEO, Child, youth and family service, NSW)

The community sector remains viable due to high amounts of unpaid work

The result of short-term, unpredictable, and limited funding is that community sector workers are carrying the costs of the crisis. Resourcing arrangements do not meet the true and full cost of delivering services. Without appropriate funding and staffing levels, paid workers have to meet demand, and offset funding shortfalls, by performing large amounts of unpaid work. More than half (55%) reported that in the last week, they performed at least one hour of unpaid work in addition to their paid time, and many workers were making large unpaid contributions.

Most staff are working extra unpaid hours every shift to meet the existing need. We are not happy about this, but can’t leave people suffering. (Frontline worker, Ageing, disability and carer service, WA)

- On average, CEOs contributed 11.6 hours of unpaid work in the previous week, in addition to 35 hours of paid time (25% of total hours worked were unpaid).

- Frontline workers averaged an extra half day of unpaid work per week (3.5 hours) in addition to an average of 31.8 paid hours.

Workers are often paid to work part time, despite working full time hours. Higher hours of unpaid work increased the likelihood of workers reporting that they are not paid fairly for the work they do. Under-investment in the sector is not new, but the pandemic has revealed heightened risks of workforce attrition and burnout.

Job security remains a major concern

Equally, the funding environment is undermining many workers’ job security and confidence in their near-term future.

- 2 in 5 community sector workers worry about the future of their job (41%)

- Most fixed-term employees (73%) have employment contracts linked to the funding cycle, but this is more common among frontline practitioners and team leaders (83% and 91% respectively)

- Job security is better among those with longer histories of work in community services. However, it is not clear whether this is because job security improves over time; or whether new recruits are entering jobs with poorer security and will maintain lower levels of job security throughout their careers.

Recruitment and retention of workers is a challenge

The overall situation outlined above makes recruitment and retention a major ongoing challenge.

- Most participants (71%) said they intend to remain in their role in 12 months. However, 29% of respondents said they plan to leave their role, with 9% planning to leave the community sector altogether.

- CEOs are most likely to intend to remain in their role in 12 months (86%). Staff in communications, policy, project, or research roles are least likely (51%).

- Two-thirds of frontline practitioners (67%) intend to remain in their current role in twelve months.

Business development, evaluation and research, contract managers, tender managers, policy and government relations roles – these are the niche skillsets that are very difficult to fill, yet are absolutely essential for long-term success in the sector. [We have an] inability to compete with private sector pay and conditions which leaves a huge skills gap. (Senior manager, Child, youth and family service, Qld)

Some workers plan to leave their role to use new skills, find new challenges or seek promotion. Most however are leaving due to problems in their current job or organisation, including insufficient paid hours and because funding uncertainty means contracts are short term and there is no pathway to permanency. Other reasons for intending to leave include work intensity, and lack of professional development.

Leaders described difficulties recruiting and retaining a wide range of staff including mental health clinicians, advocates, lawyers, financial counsellors, carers, social workers, and allied health workers. It is also difficult to fill administrative, communications, payroll and human resources roles, and fill project officer, team leader and program manager roles. Some leaders have found it difficult to find suitable staff to fill vacancies. They noted difficulties finding staff who had specific employment or lived experience, or experience working with particular client groups or in highly complex circumstances. Often, leaders put these difficulties down to low pay, short contracts and part-time hours on offer.

Our community services in my area are very well connected and we are all putting our hands in the air wondering how we can help our clients. We need more funding, more workers, more housing and our clients with serious health issues need access to more money than jobseeker. All of our clients on Centrelink are in poverty and are at risk of homelessness. …The system is broken and we are heading full steam into a serious crisis. We need more mental health support and more peer support services for the huge majority that need help but don’t qualify for the NDIS or disability payments. (Frontline worker, housing and homelessness services, QLD)

The survey findings reflect structural dilemmas that have compounded for years and stand in the way of Australia’s pandemic recovery. The ACSS has shown that the failure of government to meaningfully address community priorities, and the premature withdrawal of government support, has taken a toll on communities and placed the community sector under immense strain. A refreshed and reenergised relationship between the sector and government is needed to properly acknowledge and value the central role the sector plays in people’s lives and in creating better public policy.

Conclusion

The survey findings reflect structural dilemmas that have compounded for years and stand in the way of Australia’s pandemic recovery. The ACSS has shown that the failure of government to meaningfully address community priorities, and the premature withdrawal of government support, has taken a toll on communities and placed the community sector under immense strain. A refreshed and reenergised relationship between the sector and government is needed to properly acknowledge and value the central role the sector plays in people’s lives and in creating better public policy.

Our community services in my area are very well connected and we are all putting our hands in the air wondering how we can help our clients. We need more funding, more workers, more housing and our clients with serious health issues need access to more money than jobseeker. All of our clients on Centrelink are in poverty and are at risk of homelessness. …The system is broken and we are heading full steam into a serious crisis. We need more mental health support and more peer support services for the huge majority that need help but don’t qualify for the NDIS or disability payments. (Frontline worker, housing and homelessness services, QLD)

[1] Data on increased demand for community services from the same survey is in a companion publication, see Cortis N and Blaxland, M (2021) Meeting demand in the shadow of the Delta outbreak: Community Sector experiences. Demand Snapshot 2021. Sydney: ACOSS. Previous reports from the Australian Community Sector Survey can be found at https://www.acoss.org.au/australian-community-sector-survey/

[2] Klein, E., Cook, K., Maury, S. and Bowey, K. (2021) An exploratory study examining the changes to Australia’s social security system during COVID-19 lockdown measures, Australian Journal of Social Issues. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ajs4.196; Grudnoff, M. (2021) Opportunity lost: Half a million Australians in poverty without the coronavirus supplement, Discussion paper, The Australia Institute, https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2021-03/apo-nid311627.pdf

[3] Davidson, P., (2022) A tale of two pandemics: COVID, inequality and poverty in 2020 and 2021, ACOSS/UNSW Sydney Poverty and Inequality Partnership, Build Back Fairer Series, Report No. 3, Sydney.

Part 2

Service delivery and the Delta Outbreak

Since 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic has forced community services to operate differently as demand for services greatly increased. The report’s data was collected in September 2021, following the Delta outbreak and prior to the Omicron wave. At this time, lockdowns continued to restrict individual movement and constrain face-to-face service delivery in many parts of Australia. Concurrently, some communities struggled to access vaccinations, and children in the more populous states were undertaking remote learning Survey participants were asked about the pressures faced by the people and communities they supported during 2021, including the impacts of disruptions caused by COVID-19. Unsurprisingly, data attests to substantial challenges on all fronts and that the impact of the pandemic was felt throughout the country. In the absence of appropriate government support, the social and economic costs of the crisis fell onto communities and the local organisations supporting them. While survey participants located in jurisdictions with the longest lockdowns described particularly difficult circumstances due to COVID-19, participants in other jurisdiction also commented on the impact of border closures, economic hardship, stress, and uncertainty.

COVID really just bought into focus much which was already present: poverty, inadequate income support (particularly in regional/remote communities where there is very little work even in good times), domestic violence, mental health issues. (Office support worker, Community development services, WA)

There is just a growing fatigue everywhere that is taking its toll. We have to get back to normal, and fast, or the new normal will cripple the community services sector. (CEO, Child, youth and family services, QLD)

For some respondents, grappling with COVID-19 came during or swiftly after dealing with natural disasters. This placed enormous pressure on impacted communities and tested the capacity of the local organisations to support competing and complex individual need (see the following text box encapsulating one particular experience in detail). Overall challenges were exacerbated by the premature discontinuation of government supports, which disrupted models of service delivery established in the earlier phase of the pandemic. As one CEO explained:

In 2020 some services got some increased funding for workers to support more clients [but] this ended in July 2021 so those staff were lost. We have no hope of meeting the increased demand without more workers and funding (CEO, Child, youth and family services, NSW)

Respondents commonly described housing, mental health, and family and domestic violence as key concerns for local communities, as well as loss of income, withdrawal of additional payments like the Coronavirus Supplement and increased costs of living. For example, a WA participant noted that:

Although fortunate in WA to have not experienced extended lockdowns, lack of housing, decrease in JobSeeker, increased FDV and increased mental health challenges are all notable. (CEO, Housing and homelessness service, WA)

Housing shortages

I work in a community that was directly threatened by the Black Summer fires, hit hard by COVID 2020, just started to bounce back and then we had devastating flooding, then COVID 2021. The community is resilient and there is a genuine desire from most community members to help others. The organisation required to channel this good will: i.e. organising donations, organising volunteers, organising getting goods to people (in a COVID safe way) is extremely challenging. The greatest pressure reported is decrease of family finances, followed by increasing sense of isolation and loneliness and poor mental health. We haven’t been able to assess the impact on our young people as we cannot engage with them in large numbers. The number of women presenting with issues around FDV has decreased. This is worrying as local police are anecdotally reporting increased call outs (no stats available yet). We have heard from many of our frail aged and disabled residents that their provision of home care has decreased in the COVID lockdown period, which is also worrying. Alcohol consumption appears to be increasing. (CEO, Community development service, NSW)

Though not our main focus or traditionally an issue we’ve had much involvement in supporting families with, housing and homelessness has been an overwhelming concern this year. At one point, we were expecting about 80% of the families we supported to be homeless within 4 weeks. (Project officer, Child, youth and family services, WA)

Many regional providers reported that people leaving urban areas due to the pandemic placed pressure on local rental markets.

COVID-19 has not impacted the NT in the same way it has impacted other jurisdictions. However, during 2021 there has been an influx of interstate people relocating to the NT to avoid COVID-19 lockdowns – primarily in Sydney and Melbourne. This has significantly increased the cost of housing in the Territory, and significantly decreased the availability of affordable housing options. This has particularly made it difficult for young people, who may have limited rental history, to afford and secure housing. (Policy officer, Legal, advocacy or peak body, NT)

We are seeing a real housing crisis – people leaving Sydney to live in regional areas are pushing local people out of the private rental market and pushing the price of private rentals up with no regulation. We have several clients who have been given short termination notices, and have limited capacity to re-enter the private rental market due to the competitive pricing. Families are living in cars, couch surfing and living in unsuitable conditions as a result. (CEO, community development service, NSW)

The movement of people to [regional town] has put more pressure on an already struggling housing situation (Frontline worker, Legal, advocacy or peak body, QLD)

Experiences of housing shortages in 2021 reflected the fact that long-term affordable housing options remain severely limited in all jurisdictions.

There is an increasing number of families looking for accommodation. They often find themselves competing with 25 to 100 applications per property. Homeless people in the city are given short-term COVID accommodation and then put back on the streets once COVID restrictions have lifted. (Frontline worker / practitioner, Financial support and counselling service, SA)

[In our area], the cost of housing has skyrocketed & affordable housing is impossible to find for the most disadvantaged. Homelessness, rough sleeping, at risk, etc is growing (we are among the highest area for rough sleepers in Victoria). This is despite the programs that have targeted rehousing the homeless. (CEO, Financial support and counselling, VIC)

Lack of housing and low threshold accommodation options for very vulnerable people further exacerbated by COVID and lack of funding for additional support in the sector until housing becomes available. 17k people on the housing waitlist and some of our homeless community don’t have housing applications in, have been removed and/or can’t assess supports to assist them with these things. (Senior manager, Housing and homelessness service, WA)

Mental health Participants reported a continued rise in need for mental health support among community members, particularly in states affected by long lockdowns. Participants were frustrated by barriers their communities faced in accessing suitable supports.

Service users have [told us of] their concerns about COVID-19 and how it has negatively impacted their day to day lives, and we, as the service, have identified the lack of mental health support [as an issue] during COVID-19. We can only do so much with our staff, and capabilities and have felt like larger organisations/ business were less accessible for service users this year. (Frontline worker, Community development services, QLD)

Survey respondents explained how families they supported grappled with the mental health impacts of home schooling, working at home and the ever-present worry of job loss and further poverty, made more serious by the withdrawal of certain government support payments.

We work closely with single mothers and their children who are facing huge and cumulative challenges this year. One example is single mothers maintaining paid employment by working from home and simultaneously schooling one or more children and sometimes also caring for a toddler. The burden is enormous, employer consideration has frayed, and some of these women are not eligible for any Centrelink help and even if they were, without a Coronavirus Supplement, or JobKeeper, they would lose paid work and plunge into poverty and risk losing their housing. (Team Leader, Child, youth and family services, VIC)

Family and domestic violence Participants reported that mounting pressures on families due to prolonged housing stress, loss of employment, rising costs of living and the multiple difficulties posed by the pandemic, had impacted on the need for family and domestic violence support.

Impact of lockdowns on families under pressure and at risk of violence is profound… impact of school closures is also profound. (CEO, Child, youth and family services, VIC)

The pressures that are part and parcel of domestic violence have been exacerbated by being in lockdown with the perpetrator. (Practitioner, Legal support service, NSW)

Increased rates of family and domestic violence, and increased severity of that violence causing significant harm to women and children. (Practitioner, Financial support and counselling, QLD)

Less organisations are travelling to remote communities in the NT so people are falling through the gaps. Even basic things such as pension cards are not happening (CEO / Executive Director / Executive Officer / General Manager, Legal, advocacy and peaks (incl. community legal service, consumer advocacy, policy advocacy, peak body), NT)

Digital divide Survey participants across the country rearranged service delivery to support clients remotely. This adaptation ensured continuity of care for many existing clients, and had flow on benefits such as connecting with people who previously faced access barriers.

COVID has enabled us to work more ingeniously with clients. Clients and staff are better at using technology. Staff are now better able to support clients in very remote areas through telehealth, counselling etc., using technology. (Team Leader, Child, youth and family services, QLD)

Some of the benefits [of online and remote service delivery] have been greater inclusion of rural staff and people with disabilities as meetings and services moved online. (Senior manager, Child, youth and family services, VIC) However, participants also observed that a transition to online service delivery highlighted the digital divide. Many clients were unable to access electronic devices, afford the necessary data packages or did not feel confident using digital platforms to access services. For example:

The requirement for all community members to access government supports (e.g. Centrelink) digitally is based on an incorrect assumption that members have access to digital devices, data and digital capacity. Services funded by government must commit to improving access for all – government services must be required to do the same. (CEO, Employment, education and training, QLD)

My teams assist in very complex client care (i.e. related to mental health, alcohol and other drugs, acquired brain injury, dementia, chronic disease, isolation, culturally and linguistically diverse communities, LGBTI, housing concerns etc) and case manage this diverse group of people and their issues…These clients don’t have access to technology (places such as libraries, IT computer support classes, etc close under lockdowns and other restrictions, and yet they are where clients used to access the internet and in person support). Clients we see do not have the means to fund technology themselves nor have the means to assist in IT set up and ongoing support of technology use in the home (if they indeed have a home!). Disadvantaged clients are constantly steps behind the general population and the gap is widening. (Team Leader, Health-related service, VIC)

Coronavirus supplement, JobKeeper and other government supports Participants explained how in the earlier stage of pandemic, additional government support payments for community members had alleviated considerable financial hardship. They expressed concern about their removal while the impacts of the pandemic were still being acutely felt. As this frontline worker from Victoria explained in detail, the supports previously in place had helped to reduce the load on community services.

The payments that all jobless people received in 2020 were a significant support for ALL families that we worked with. Parents no longer had to spend much of their days chasing food vouchers and financial support to pay basic bills. They could afford good food, pay all their bills easily, and then started to actually have time and emotional space for making improvements to their own ability to manage their emotions and improve family relationships etc. Doubling the jobless payment in 2020 was the number one factor in improving family functioning for the families I was working with. Family violence for many of these families decreased significantly, or ceased all together, as parents were able to meet all the basic needs of the family and could then turn to focus on medium to long term goals. It also meant that my time as a case manager was not taken up by completing multiple and time-consuming referrals and applications for funding for basic needs. I could utilise my professional time for the family actually supporting them to make meaningful changes. (Frontline worker, Child, youth and family services, VIC)

Others observed that when the payments were withdrawn, poverty and hardship in the community increased, which intensified pressures on services during 2021.

The increase in Centrelink payments was welcome for those who qualified, but when they were reduced, real hardship was the result. This also caused mental health issues and increased sense of betrayal and dismissal by government. (CEO, Ageing, disability and carer service, QLD)

Income support payments being slashed back to below the poverty line, and the delays and trickiness and complexity of the COVID supplement replacement, have left too many facing a very bleak year. (Policy officer, Peak body, TAS)

Challenges for particular groups Some participants pointed to particular groups in the community who experienced exceptional difficulties through 2021, such as people with disability and their carers, and people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. For instance, some participants in the states with extended lockdowns pointed to the additional challenges presented by learning from home for families with children with disability:

I am concerned about learning gaps for children with disability who have had prolonged learning from home. In 2020 when students returned to school, we saw a big up-swing in the number of students with disability suspended or placed on restricted hours of attendance. (CEO, Peak body, VIC)

The stresses we often see are for the families who are trying to work from home and support children/child with very complex needs all day everyday without the support of school or day programs. (CEO, Ageing, disability and carer service, NSW)

They also described the difficulty for people with disability in accessing appropriate and essential services:

A significant amount of organisations closed their doors during COVID 19 only doing phone contact. This put our clients at a significant disadvantage due to their disability. Our organisation stayed open and available throughout, which saw an increase in demand for our service. (Frontline worker, Ageing, disability and carer service, QLD)

I am concerned young children with disability are accessing NDIS early intervention later due to slower identification of developmental delays. (CEO, Peak body, VIC)

We are unable to have our clients assessed by an OT, assessments for ASD, speech, etc as all services are over a 12 month wait and the cost is high. (Frontline worker, Child, youth and family services, VIC)

There was also concern that community members from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds were struggling more than others due to difficulties accessing timely and appropriate COVID information, accessing services, or supporting children to learn from home in English.

The pressures on CALD communities associated with COVID-19 this year have been huge. Whether its expecting families who are illiterate in their own language to provide learning at home for their several children, or the difficulties of finding housing in [around here] where applicants were required to be pre-approved to even view the property (which excluded many CALD residents), or receiving critical health information significantly later than English speaking residents, thereby increasing the risk of being fined for contravening a regulation they were not aware of. (Team Leader, Migrant and multicultural services, NSW)

There was a lack of material translated in accessible forms – too much reliance on translating material into written form and posting on a website – seems government then thinks they have ticked that box. Unfortunately, there are those in CALD communities who don’t read and write in their home language. (CEO, Child, youth and family services, VIC)

Some mentioned particular concerns relating to women, and older people, within CALD communities who required additional support:

Women in CALD communities are suffering disproportionally from social isolation and mental health issues since COVID-19. (Frontline worker, Health-related services, WA)

COVID has made the lives of many of our elderly more isolated. The fear and misinformation of the media (shame on them) has forced many elderly CALD participants into social and self-isolation, even when they needed to access hospitals and doctor and attend friend and family situations, like funerals. (Policy officer, Ageing, disability and carers service, NSW)

It is within this context, of enormous social challenges facing individuals, that the community services sector continued providing support. The sector’s resourcefulness and innovation came in the face of immense challenges, as the following sections of this report will show. These challenges chiefly included ongoing difficulties accessing sufficient funding to cover costs of essential services, lack of funding security, short funding contracts, high levels of unpaid work by staff, a lack of job security and other workforce issues.

Housing insecurity, mental health challenges, and difficulties experienced by children and families came through strongly in survey results as persistent problems, in particular for groups with disability and those from non-English speaking backgrounds.

Part 3

Funding arrangements and financial security

Australia’s community sector continues to confront the COVID-19 crisis following years of inadequate funding. Too often, funding fails to sufficiently provide for overhead, administration, and workforce costs in addition to program delivery. The community sector is unfairly expected to meet community needs with an unstable funding base that does not recognise full operational costs. As most community service organisations deliver services on behalf of government, government funding is the sector’s most important income source. Three in five leaders (60%) said state or territory governments were the most important funding source for their organisation. A further 20% said Federal Government funding was most important, and this group included many larger organisations and organisations focused on areas of Federal responsibility, such as ageing and disability services (see Appendix B, Table B. 1, Table B. 2). Few organisations relied mainly on philanthropy (5%), client-based fees (7%), other commercial sources (4%), and other sources (4%). Contracting with government, and the adequacy of government funding, are therefore key issues to which the following data attests. Funding adequacy Leaders were asked about the adequacy of their main funding source for covering costs and meeting need. Leaders clearly highlighted the multiple ways funding falls short (Figure 3.1):

- Only one in five (20%) agreed that funding covers the full costs of service delivery and three quarters (76%) disagreed.

- Only 14% agreed that funding properly recognises their overheads, and 78% disagreed.

- Only 17% agreed that their main funding source recognises increasing wage costs, and 74% disagreed.

- Only 14% agreed that indexation arrangements are adequate while two thirds (65%) disagreed.

The above statistics reveal just how thin the funding model tends to be for the sector. Similar patterns of response to these questions were evident across small and large organisations, metropolitan and non-metropolitan locations, and across organisations delivering different types of services.

Figure 3.1 Leaders’ ratings of their main funding source

Shortfalls for essential service activities

Figure 3.2 details how participants saw insufficient funding impacting their organisations, and how it curtailed fundamental elements of their operations.

- In 2021, only 18% agreed that funding allows their organisation to innovate, and 65% disagreed. Disagreement was higher in 2021 than in 2019, when ACSS participants were also asked this question, and 25% agreed and 59% disagreed.[1]

- Leaders have increasingly found their funding is inadequate to attract and retain staff. In 2021, only 19% agreed with the statement “Funding enables us to attract and retain high quality staff”. This is worse than in 2019, when 25% agreed.

- Leaders of organisations for which the main funding came from a non-government source were slightly more likely than those more reliant on government to agree that funding enables them to attract and retain high-quality staff.

In addition, in 2021, many leaders reported inadequate funding for monitoring and reporting on program delivery:

- Less than a quarter of leaders (22%) said that their main source of funding supported monitoring and evaluation, while 58% disagreed.

In 2021, funding also fell short in relation to collaboration and engagement.

- Only a quarter (24%) agreed that funders work with them to understand community need and plan responses, while double this proportion (49%) disagreed this occurred.

- Only 28% said that funding supports the organisation to engage with government policy and reform processes, while 48% disagreed.

- One in three leaders (32%) agreed that their main source of funding enables genuine involvement of consumers or people with lived experience, while 46% disagreed. This shows slight improvement compared with 2019, when 29% agreed and 42% disagreed.[2]

Figure 3.2 Leaders’ agreement with statements about funding

Funding and the pandemic

When asked about receiving support to respond to emergencies, just over a quarter of leaders (27%) agreed funding supported the development of good models of remote service delivery; this was fairly consistent, with no notable differences among groups of organisations. Although many saw benefits in the transition to online service delivery, it also highlighted the digital divide (see Section 2.4). Just over a third (35%) agreed that funding had appropriately supported them to address emergencies facing their communities (see Figure 3.3). However, 43% reported that this was not the case.

Figure 3.3 Leaders’ assessment of funding in the context of the pandemic

Access to different funding sources

Leaders were particularly concerned that despite the community need generated by the pandemic, philanthropic funding has become more difficult to access (Figure 3.4).[3]

- Two thirds of leaders reported that in 2021, their organisation was finding it more difficult to access donations from the public, and donations from business.

- In addition, almost half (48%) reported consumer fees were becoming more difficult for their organisation to access, and 55% found other commercial income was becoming more difficult to attract

- While for many, access to government funding was stable, 45% said Australian Government funding was becoming more difficult to access and 40% were finding state and territory funding was becoming more difficult to access.

For each income source, only small minorities reported improved funding access (Figure 3.4).

Figure 3.4 Leaders’ ratings of changing access to funding sources

Comments on changing access to funding sources

To explore funding issues in more detail, leaders were asked to provide brief comments on how funding sources are changing, or likely to change.

Changing Government funding

Organisational leaders outlined growing challenges with state, territory or Federal Government funding. Some felt that funding opportunities were becoming increasingly scarce, or that competition was more fierce with growing numbers of organisations seeking support:

There seems to be less tenders on offer that are ongoing. More short term grants. (Senior manager, Child, youth and family service, QLD)

Because of the increases [in numbers] and competing demands from organisations seeking funds, it is becoming extremely difficult to successfully obtain further funding. (CEO, Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander service, QLD)

Others noted that funding processes and contract requirements were making government funding more difficult. This included high reporting expectations, lack of information about contract renewals, and a shift to individualised funding or ‘payments in arrears’. One explained, for example, that in this context they needed:

Resources to keep on top of looking for funding while responding to increasing demands of funders for information and reporting (particularly with COVID weekly reports in some cases). (CEO, Legal, advocacy or peak body, WA)

A lot of uncertainty around the possibility of renewing our contract that is coming up for review soon. No indication of timelines or requirements for renewal and no consultation process. (CEO, Child, youth and family service, QLD)

It seems there is a focus to make programs a “user pays” model, like the NDIS. Funders are also moving to payments in arrears, and a great requirement for us to co contribute to programs. No one seems to like paying for admin/management costs, and yet we are not viable without that back of house support. (CEO, Child, youth and family service, NSW)

As the CEO above noted, funding often does not fully cover costs. Even for those few participants who had said that state, territory, or Federal Government funding is becoming easier to access, this remained a problem, for example:

Everyone is so desperate for support we can get funding for programs quite easily. The issue is whether it is actually financially viable given costs. (CEO, Child, youth or family service, QLD)

A lot of funding opportunities will not cover expenses such as wages, shared expenses such as insurance and rent. (CEO, Legal, advocacy or peak body, NSW)

COVID19 related grants increasing, but small amounts and short term. Decrease in settlement funding despite intensification of needs. (Senior manager, Migrant and multicultural services, NSW)

Changes in non-government funding Many sector leaders wrote about changes in non-government sources of funding for their organisations, including social enterprises, service fees, fundraising and philanthropic contributions. For some, these offered new funding opportunities:

We are investing more into social enterprise business development as income generators. (CEO, Community development organisation, QLD)

We are diversifying and focusing on fee for service funding sources. (CEO, Community development organisation, WA)

Law firms are stepping up pro bono supports. (CEO, Legal, advocacy or peak body, QLD)

Some sector leaders explained that they would like to secure alternate funding sources, for some because their government funding was uncertain, but were equally unsure how successful they would be, especially in the current financial climate:

There is less money in the community and people are less likely to donate. We need block funding to keep the office doors open (not more projects to manage with no base funding) (CEO, Ageing, disability or carer organisation, ACT)

If you don’t operate in a ‘sexy’ area there’s no fundraising/ philanthropic money, and Govt money is becoming tighter and harder to win especially if you go in with a true cost (you only win tenders/grants now if you under budget and then are prepared to wear the loss). (CEO, Health-related service, ACT)

We are having to look strongly at how we diversify our funding sources and if there are things we can market. We have no clue what our state funding will look like given it has rolled over for so long and is due to go through a new tendering process. We have some commitment from the state to fund in general but no real idea of what this looks like in reality. (Senior manager, Legal, advocacy or peak body, WA)

Others described additional barriers to these sources of income and funding, mostly due to pandemic lockdowns and the COVID-19 impact on the economy.

Our social enterprise is a significant part of our business model. While we have accessed some support, we have also needed to stand staff down, and seek rent relief in order to reduce the significant losses we have experienced. (CEO, Child, youth and family service, VIC)

Training income has decreased because of COVID. (Senior manager, Legal, advocacy or peak body, NSW)

Businesses are struggling therefore their capacity to sponsor and donate is constrained. Also fundraising events are being regularly cancelled or are not as effective (i.e. online vs in person events). (CEO, Child, youth and family service, ACT)

Retail sales impacted through COVID and some fee-paying services declined during lockdowns. (CEO, Child, youth and family service, SA)

Small services Some small services argued that securing funding in their circumstances is particularly difficult. They reported that recognition of the benefits of smaller organisations was diminishing, placing their financial security at risk. As a result, they felt that funding processes favoured large organisations with substantial grant-writing, reporting and management infrastructure.

As a small not for profit, our executive officer is the person who applies for funding. While we have had access to more funding sources, we haven’t been successful. Is that due to being small or a lack of expertise in the application. We also have to assess the use of the executive officer ‘s time for applications. One Federal tender has had to be done 3 times and we are still waiting to hear if we have been successful or not. (CEO, Employment, education and training service, VIC)

Government grants are increasingly going to large scale organisation, but the value for money is missing as so much of the grant disappears in these large organisations to infrastructure. More often than not the question of quality and economy are better served in smaller specific organisation. (CEO, Community development organisation, NSW)

The funding applications have become a lot more complex and demanding. The criteria expected seems to have become so bureaucratic rather than realistic. They seem a lot more geared towards large not for profits who have the infrastructure and specialised staff to be able to put forward a good grant application making it harder for the smaller grass roots organisations to succeed. (CEO, Community development organisation, NSW)

Financial position in 2021 [4] Around one third of organisations (34%) reported their financial position stayed about the same, while 31% reported improvement. A total of 29% of leaders said their financial position had worsened (Figure 3.5). However, perceptions differed across states and territories. Finances improved for 49% of organisations responding from Victoria, likely reflecting recovery from the challenges of prolonged shutdown in 2020. Among those from NSW, a relatively high proportion experienced deterioration in financial status (38%) and a lower proportion reported improvement (24%), likely reflecting the depth of the Delta outbreak.

Figure 3.5 Changes in organisations’ financial position in 2021 (leaders’ reports)

Outlook for 2022

Even before the Omicron phase of the pandemic, 29% of leaders were anticipating that finances would worsen in 2022, while 37% expected no change and 20% expected to see improvement (Figure 3.6). Expectations were lowest among organisations in the ACT, where 50% of leaders expected their financial position to worsen in 2022, likely reflecting the lockdown and growing impact of the pandemic around the time of the survey (Figure B. 1). Among organisations dependent on Federal Government funding, two in five (40%) expected their finances to worsen in 2022 (Figure B. 2).

Figure 3.6 How organisational finances are expected to change in 2022

Note: Data is leaders’ perspectives (n=507)

Organisational leaders were given an opportunity to comment about the financial outlook for their organisation, and the factors affecting it. A small selection of participants made positive comments underlining the outcome of their organisation’s efforts to improve sustainability, for example:

In 2021 we converted from incorporated association to company limited by guarantee so we can operate nationally. We’ve also established a social enterprise arm to market and work with the general public on a profit-for-purpose basis to support our fundraising and financial sustainability efforts. (CEO, Child, youth and family service, SA)

We have significant reserves which enable us to both invest and innovate as well deal with sizeable cash flow issues as a result in changes in Government funding regimes for aged care – our improving financial position is as a result of good investing decisions and not Government funding increases – these gains support our benevolent role. (CEO, Ageing, disability or carer organisation, SA)

For nearly all who commented however, the financial outlook was either bleak or uncertain. Challenges often related to government funding, including uncertainty around contract renewals, and the adequacy of funding to cover rising wages and superannuation:

The major factor affecting it is 40% of our funding is tied to various state and fed funded programs with 30 June 2022 end dates and no consultation on renewals. (CEO, Legal, advocacy or peak body, QLD)

We got an increase in funding but with pay rises, super increase and rent increase it hasn’t given us much in the way of additional resources. (CEO, Legal, advocacy or peak, WA)

Most sectors are being reviewed or waiting on the outcomes of reviews…. Much is unknown. (CEO, Housing, or homelessness service, TAS)

We are seeing significant increases in costs through salary rises, IT requirements, superannuation contributions and long service leave contributions but funding is not keeping up. (CEO, Legal, advocacy or peak body, ACT)

Most participants spoke of the additional difficulties that COVID-19 had posed for the financial security of their organisations. Some had received extra support or flexibility from government in 2020 and 2021, but these had mostly come to an end, and they were concerned about the future without them. For example:

Underspends from government grants have been rolled over which is great but once COVID is gone I expect this flexibility to decrease as restoring the budget becomes a focus. (CEO, Ageing, disability and carer organisation, SA)

Our situation improved temporarily due to government support during COVID. There is no indication that these supports will be continued – or even repeated following the next disaster. (CEO, Legal, advocacy or peak body, NSW)

Thanks to JobKeeper our funding increased but otherwise we would have run at a loss. (Senior manager, Community development service, Qld)

The pandemic has temporarily increased funding to COVID specific programs which has buffered reductions in other areas. The concern is for sustainability of organisations as these programs end. (Senior manager, Financial support and counselling, VIC)

Some had reduced income because COVID-19 lockdowns had limited access to donations or resulted in reduced operations of their social enterprises.

COVID has placed massive strain on business with 64% reduction in income streams. (CEO, Child, youth and family services, ACT)

The pandemic has impacted the number of donations that we would normally receive to provide additional support to young people. (CEO, Housing and homelessness service, QLD)

We have not been able to open our fundraising Op Shop during the COVID-19 pandemic and this provides a much needed income stream. (CEO, Community development service, NSW)

In a context in which community service organisations are already operating with very tight budgets, unsure when or if their contracts will be renewed, some leaders expressed grave concern about the financial outlook for their organisations.

I’m seriously worried. I don’t want to stand down staff because you put so much time and money into training them and if you stand them down they will leave but keeping paying them through this round of lockdowns has almost depleted our retained earnings that we have spent 20 years saving. (CEO, Health-related service, ACT)

The pandemic has had a negative impact on the organisation, hence outlook remains uncertain. (CEO, Child, youth and family services, NSW)

If we continue to rely on government funding to the same extent, we have a short future. (CEO, Child, youth and family service, VIC)

[1] Cortis, N. & Blaxland, M (2020): The profile and pulse of the sector: Findings from the 2019 Australian Community Sector Survey. Sydney: ACOSS

[2] Cortis, N. & Blaxland, M (2020): The profile and pulse of the sector: Findings from the 2019 Australian Community Sector Survey. Sydney: ACOSS.

[3] For more information about addressing demand and meeting need, see Cortis N and Blaxland, M (2021) Meeting demand in the shadow of the Delta outbreak: Community Sector experiences. Demand Snapshot 2021. Sydney: ACOSS. https://www.acoss.org.au/australian-community-sector-survey/ [4] Note that the survey was conducted in September 2021, prior to the Omicron phase of the pandemic.

Part 4

Contracting

Temporary changes to contracting processes were made by some government funders to allow community organisations to respond to the pandemic’s impacts more effectively. Some services received additional flexibility in the use of funds, as well as contract extensions to create further certainty. However, despite such short-term improvements, government contracting arrangements remain a source of significant frustration for community sector leaders. Persistent issues include contract duration and renewal processes. Short contracts and minimal notice periods for renewals are inimical to the services delivered by community organisations, making it difficult for them to plan work, attract and retain skilled staff and deliver lasting positive outcomes for the people they help. Contract duration When leaders were asked if they agreed with the statement “Funding timeframes are long enough”, only a quarter (26%) agreed, and the majority disagreed (59%). Many organisations continue to rely on short term contracts, despite the benefits afforded by longer term contracts for service delivery, planning and staff retention.[1] Five-year agreements are seen favourably in the community sector. For this reason, the survey asked leaders to report the duration of their longest contract with government (see Table 4.1, with a breakdown by service type in Table B. 6):

- 13% of leaders said their organisation’s longest contract was less than 12 months; and

- 10% said their longest was up to 24 months in duration.

- 40% of leaders said their organisation had a contract with government which was 5 years or longer in duration.

Among those focused on child, youth and family services, a relatively high proportion had at least one contract of five years or more (57%), as did those focused on community development (54%). In contrast, low proportions of organisations providing ageing, disability, and carer services (21%) had five-year contracts, along with services focused on migrant and multicultural services (17%) and those delivering financial counselling and support (19%). Five-year contracts were also less common among smaller organisations, those in Victoria and the ACT (see Table B. 3) and organisations for which the main funding source was the Australian Government.

Table 4.1 Leaders’ reports of the organisation’s longest contract currently in place

Contract renewals

Leaders were asked to recall the last time a funding contract came up for renewal, and to indicate how many weeks in advance the organisation was notified as to whether it would be renewed. One in eight (12%) said their organisation received no notice at all, and a further 9% received less than 2 weeks’ notice (Table 5.1). The largest groups received between 2 and 8-weeks’ notice, which gives a very small amount of time for organisations and staff to plan. Indeed, it has previously been recommended that at least six months’ notice of renewal or cessation of funding be provided.[2] Only 5% of leaders said their organisation were notified about renewal at least six months in advance (Table 5.1).

Table 4.2 Advance notification about most recent contract renewal

When asked to comment on contracting issues, some leaders focused on the difficulties posed by short contracts for planning and staffing. They observed that planning for service delivery and retaining staff was difficult when contracts are short, for example.

Contracts are far too short for the sector and affect the retention of staff and the planning of services. Contracts need to be longer in length and give room for more flexibility such as innovation and responding to client need as it arises. (CEO, Health-related service, ACT)

The lack of definitive commitment to long term funding is debilitating and has long term negative impacts on the alcohol and other drugs sector. (CEO, Health-related service, SA)

The length of funding contract is not sufficient for long term service planning. (Senior manager, Community development service, NSW)

Most, however, chose to discuss the short notice they received in advance of contract renewals. Leaders typically observed that they were advised about a contract renewal with too little notice. Several even reported they did not officially receive notice, and assurances of formal notification, until several months into the new contract period. This presents a series of compliance risks for organisations in their daily operations.

Unofficially we are told months in advance, but in reality sometimes paperwork comes after the funding period has started. So technically we should have laid off staff. (CEO, Legal, advocacy or peak body, WA)

We were told it would be renewed, but there would be less $ and still don’t know the final figure – 10 weeks into the contract. (CEO, Health-related service, NT)

Many of our annual grants come three months into the financial year. (CEO, Employment, education and training provider, NSW)

Many commented that short and substantially delayed notice causes difficulties with fulfilling industrial relations obligations.

Communications start early, however the final approval of a contract renewal is usually quite short notice. Employment positions are attached to contracts and the short notice does not allow for the fulfilment of IR processes to be done appropriately. (CEO, Child, youth and family service, Qld)

While organisations tolerate late notice as a gesture of goodwill to funders, late notice does generate challenges for organisations, and can contribute to staffing difficulties.

Often very short timelines here – while funders generally come through and there’s often goodwill in my area it does create anxiety for staff re security of tenure. (CEO, Legal, advocacy or peak body, VIC)

Late notice, last minute changes to reporting requirements – we can’t keep good staff and it costs us every time they change what we need to report on. (Senior manager, Legal, advocacy or peak body, WA)

As the above Senior Manager from WA observed, this makes planning, budgeting, and service implementation difficult. Other respondents had similar comments:

There is not enough notice and then there are high expectations to get new services up and running with minimal lead in time. (CEO, Ageing, disability and carer organisation, SA)

Where do we start? Some contracts date back to 2009. Others have been rolled forward for another 3+1+1 without any amendment to terms and conditions. Some contract rollovers have not been confirmed until less than 1 month prior to termination, making it difficult to budget and to retain workforce in the face of a terminating contract. (CEO, Housing and homelessness service, WA)

Contracts and advocacy For many community sector organisations, the nature of their contracts and funding arrangements, influences their willingness or capacity to undertake systemic advocacy on behalf of their clients. Alongside service delivery, advocacy is vital to improve social policy settings and service design. The community sector has immense expertise to offer government, and this has been especially valuable as Australia responds to the multi-faceted crises posed during the pandemic. However, many in the sector continue to have a fraught experience in undertaking advocacy and maintaining funding contracts with government. More than a quarter (27%) of leaders said their organisation has at least one funding contract in place that precludes the use of funds for systemic advocacy. Half (49%) said they did not have a government contract that did this, while 24% were unsure. Among organisations based in NSW, a higher proportion reported having a funding contract that precluded advocacy (34%). Contracts precluding advocacy were also more common among organisations focused on health; employment, education, and training; housing and homelessness, and migrant and multicultural services. For each of these services, over 30% of leaders said their organisation had at least one contract in place precluding use of funds for advocacy. Even though systemic advocacy is well recognised as integral to community sector work, many organisations approach it cautiously. A total of 38% of leaders agreed with the statement “We need to be cautious about engaging in systemic advocacy because of our funding arrangements”. This result is slightly lower than 2019, when 43% of leaders agreed or strongly agreed with this statement.[3] In 2021, caution was a little higher in organisations for which the main funding source was a state or territory government. A total of 43% of leaders in organisations mainly funded by state or territory governments agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, compared with 38% of those mainly funded from Australian Government sources, and 24% of those funded mainly from commercial, philanthropic, or other sources. Caution about engaging in systemic advocacy can alter the behaviour of organisations. One in five leaders (19%) said their organisations had avoided engaging in systemic advocacy due to concerns about possible repercussions. The figure was highest among organisations focused on housing and homelessness services, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander services. When they commented on their organisation’s advocacy, leaders expressed their deep commitment to this aspect of their work, and gave examples of their approach and achievements:

Advocating for clients can improve systems and is the core of change. We should be proud to elevate the voice of those vulnerable. (CEO, Migrant and multicultural service, VIC)

They also referred to the risks, including threats to their funding:

We very, very strongly advocate for the service users, families, and carers we support, but have definitely felt threatened by some of the language used by our funders. (CEO, Child, youth and family service, NSW)

We continue to advocate on public policy issues that impact disadvantaged South Australians because it is our job to do so irrespective of the risks. (CEO, Child, youth and family service, SA)

Overall, participants explained they weigh up several factors when approaching advocacy work – the nature of the issue; contractual limits; how publicly they might be speaking; and their relationship with, and understanding of, the government in question. Many indicated that they advocate in certain circumstances and not others and had to ‘tread carefully’.

Advocacy is important to us and in many areas, we haven’t let funding have an impact. There are some specific areas where it is explicit that we don’t get involved e.g., migrant issues. (CEO, Child, youth and family service, VIC)

Our preferred approach is to engage in dialogue in a respectful and professional way with government. While not afraid to raise issues we are acutely conscious that we need to tread carefully in this regard. (CEO, Ageing, Disability and Carer service, Qld)

We are lucky that part of our role is about systemic advocacy, however we are cautious to not be overtly critical of our major funding partner. (CEO, Employment, education and training organisation, VIC)

We feel that our state government funding bodies are open to engagement and do not project a ‘gag’ culture. We are much more cautious with our Federal funded programs [because] we do not have consistent experiences of open consultation or receptivity to challenging feedback for systemic improvement. (Senior manager, Community development service, NSW)

[1] See Blaxland, M and Cortis, N (2021) Valuing Australia’s community sector: Better contracting for capacity, sustainability and impact. Sydney: ACOSS at https://www.acoss.org.au/australian-community-sector-survey/

[2] See foreword by Cassandra Goldie in Blaxland, M and Cortis, N (2021) Valuing Australia’s community sector: Better contracting for capacity, sustainability and impact. Sydney: ACOSS https://www.acoss.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/ACSS-2021_better-contracting-report.pdf

[3] See Cortis, N. & Blaxland, M (2020): The profile and pulse of the sector: Findings from the 2019 Australian Community Sector Survey. Sydney: ACOSS

Many participants reported that job insecurity had affected staff in their organisation in 2021. 32% had seen job losses or non-renewal of contracts, 29% reported loss of work for casual or fixed term staff, 20% reported reduced hours for paid staff, and 17% had observed a freeze on staff recruitment.

Two in five participants (41%) said they worry about the future of their job.

Part 5

Workforce Issues

The ACSS data reveals the enormous pressure and strain that community sector workers were under in 2021. One major practical challenge included providing both remote and face-to-face services to meet increasing need in the community. Employment challenges have included job insecurity, high workload and pay rates that do not reflect the value of their work. Of significant concern, the data shows that community sector workers and leaders are offsetting funding shortfalls by performing large amounts of unpaid work. Unpaid work As reported previously[1], frontline workers have been particularly stretched in the pandemic. To compensate for insufficient and short-term public funding challenges, it has been the sector’s high level of commitment, namely staff contributing additional, unpaid hours that has made it possible to address rising community need. A total of 22% of participants reported that they had seen increases in unpaid overtime in their organisation during 2021 (Figure B. 3). Participants noted the way their operational environment continued to be predicated on unpaid work. For example:

There is an expectation of non-management staff to go above and beyond, work longer unpaid hours and undertake duties outside their pay scale. (Administrator, Legal, advocacy or peak body, QLD)

[We have] more documentation, and not enough time to do it in the work shift, so it’s been done in unpaid time after the shift finishes (Frontline worker, ageing, disability and carer service, SA)

Loss of volunteers due to the pandemic, in the context of rising demand, also impacted on the time and tasks required of paid staff:

We are performing more voluntary hours alongside our paid hours, with loss of volunteers and increased demand for services. (CEO, community development service, NSW)

Managers appear to be carrying a particularly high workload, for example:

We have to continually work to achieve additional grants funding, both government and philanthropic. This work has to be done primarily by the manager on an unpaid basis. (CEO, Child, family and youth service, NSW)

Small organisations want to do more work, but when they don’t have the appropriate administration to support the work it creates the requirement for management to do extra unpaid hours to meet the contractual and organisational obligations. (Member of a management committee, Child, family and youth service, QLD)

ACSS 2021 data about working time substantiates these perspectives. When asked to report the number of additional unpaid hours worked in the last week, more than half reported one hour or more (55%). Many however contributed several hours. On average, participants performed an average of 32.9 paid hours per week, and an additional 6 unpaid hours (average of 38.9 hours of total work per week). Of the total hours worked, around 15% was unpaid, amounting to near an additional day unpaid, per week, for every worker. Unpaid hours were particularly high among organisational leaders (Table 5.1). Among CEOs, 90% performed at least 1 hour of unpaid work in the previous week, and on average, CEOs performed 11.6 unpaid hours per week, amounting to 25% of total work hours. Among frontline practitioners, a little over half (52%) performed at least one hour of unpaid work in the previous week, and on average, practitioners contributed 3.5 hours of unpaid work per week – amounting to around half a day or 10% of total hours worked. Data for other roles is in Table 5.1. Unpaid hours point to serious structural issues with how community sector organisations operate with insufficient funding and inadequate contractual arrangements. Unpaid hours were relatively low among those who agreed there were enough staff to complete the work, but above average among respondents who did not agree there were enough staff to get the work done (Table B. 4). Unpaid work is also associated with participants’ perceptions of pay. Those who agreed with the statement “I am paid fairly for the work that I do” performed fewer unpaid hours than others. Correspondingly, those who did not feel they were paid fairly reported higher average unpaid hours (Table B. 5). Not surprisingly, then, working conditions were often cited by participants considering moving into other jobs (see Section 5.4).

Table 5.1 Hours of paid and unpaid work, by role

Job security

Many participants reported that job insecurity had affected staff in their organisation in 2021. A third (32%) had seen job losses or non-renewal of contracts, 29% reported loss of work for casual or fixed term staff, 20% reported reduced hours for paid staff, and 17% had observed a freeze on staff recruitment (Figure B. 3). In addition, two in five participants (41%) said they worry about the future of their job (Figure 5.1).

Short term (1 – 3 year) contracts are harder as you get older – it would be good to know at least 3 months before a contract ends if it is going to be refunded – I cannot wait until the last minute to see anymore as I am concerned about picking up another contract at my age. I have left jobs in the last two months of a contract only to know that the contract has been refunded and I could have stayed – it is unnecessarily stressful and the sector loses out on experienced staff. (Team leader, health-focused service, QLD)

Figure 5.1 Agreement with the statement “I worry about the future of my job”, by employment arrangement

Concern over job security was more common among those employed on a fixed-term basis, a group which constituted around a quarter of participants (26%, Table B. 7).[2] Among those employed on a fixed term basis, almost three-quarters (73%) said that the duration of their contract was linked to the funding cycle. However, this differed across roles: frontline practitioners and team leaders or coordinators of services or programs were most likely to have their contracts linked to the duration of the funding cycle (83% and 91% respectively, see Figure 5.2). Comparatively few CEOs (42%) who were employed on a fixed term basis said this was linked to the funding cycle, indicating use of fixed-term contracts for other reasons.

Figure 5.2 Fixed term staff whose contract duration was linked to the funding cycle

Job security was better among those with longer working histories in community services. Figure 5.3 shows the proportion of participants who were employed on a permanent basis was higher for those who had worked for longer in the community sector, and the proportion working on a fixed term basis was lower. This may reflect the ways employment security improves over time, but may also reflect cohort effects, whereby those most recently entering the sector are entering roles with poorer security.

Figure 5.3 Workers employed on a permanent and fixed term basis, by total years worked in community sector

Other working conditions

Adequacy of staffing