ACOSS BRIEFING, OCTOBER 2017 Download in PDF

No child need live in poverty

Australia has experienced 20 years of sustained economic growth and is one of the wealthiest countries in the world.

Despite our wealth, the latest ACOSS Poverty in Australia report (2016) found of the three million people living in poverty in Australia, 731,000 are children, representing one in six (17%) of children under the age of 15. This figure has increased by 2 percentage points over the past ten years. ((ACOSS & SPRC (2016): Poverty in Australia))

Single parent families locked out of paid work are at particularly high risk of poverty. Forty per cent of all children in poverty in Australia live in single parent households.

We can and must do better.

Alleviating poverty has a positive impact on everybody

Children and young people deprived of food, clothes and other materials may reduce their engagement with school due to hunger, shame or being excluded or marginalised, impacting children’s development, educational, and eventually employment opportunities. ((Redmond et al (2016): Are the kids alright? Young Australians in their middle years))

Evidence shows that reducing poverty leads to better health, education and employment outcomes for children, even if they have equal access to health and education.((Kerris Cooper and Kitty Stewart (2017): Does Money Affect Children’s Outcomes? An update London School of Economics))

We call on government to take swift and determined action to reduce child poverty.

Australia’s child poverty trend is heading in the wrong direction. We can, and must, reverse the tide.

The Federal government can do this by:

- Committing to reducing poverty by at least 50 per cent by 2030, in line with the Sustainable Development Goals

- Increasing Newstart Allowance, including for single parents

- Establishing a single parent supplement that increases as children grow older and they cost more to support

- Indexing working age and family payments to wage movements as well as prices

- Improving employment and training programs for single parents, including career counselling and vocational training

- Guaranteeing secure affordable housing, including working with state and territory governments to abolish no-cause evictions

- Restoring two days of weekly subsidised child care available to parents not in paid employment.

The evidence is there. It can be done.

30 years ago, child poverty was reduced by 30 per cent.

This year marks 30 years since former Prime Minister Bob Hawke made the commitment that “no child will be living in poverty’’.

This statement was criticised as too ambitious, but the reforms his government introduced reduced child poverty by 30 per cent.

The key reforms of the Hawke government included:

- A new supplement for low-income families to help meet the cost of living

- Increasing existing family payments to reflect the cost of children

- Linking family payments to wage growth, to maintain pace with the cost of living and community living standards.

- Rent assistance to help families and others on low incomes to cover the cost of rent.

From 1987, spending on family payments grew because payment rates were increased and steps were taken to ensure families accessed entitlements.((Peter Whiteford (2017): draft article for publication in The Conversation on 16 October 2017.))

The core principle was that family payments should at least cover the basic costs of children in a family in a low paid job, or lacking paid employment altogether.

Broader policies targeting parents and children were implemented, including fostering carer friendly work places, expanding childcare and improving fee relief, and a new program offering career counselling, education and training for sole parents.((Peter Whiteford and Bettina Cass (2009): Social Inclusion and the Struggle against Child Poverty: Lessons from Australian Experience))

Since then, governments have lacked the ambition to reduce child poverty.

Thirty years since these bold reforms, child poverty is on the rise.

Today, many children experience severe hardship. Parents and children skip meals, children miss sporting and school activities, heaters, fridges and phones for those who have accommodation are being turned off, and families are being evicted.

Social security payments for families, and particularly single parent families, have been slashed in recent years, with cuts included in almost every federal budget since the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. The reduction in social security spending combined with low and stagnant wages, insecure work, and the high cost of living has pushed parents and their children into poverty.

There is deep concern for the increasing number of children living in poverty.

Child poverty in Australia increased by 2 percentage points over the decade 2003-04 to 2013-14.

The share of children living below the poverty line (set at 50% of median household income) fell from 14 per cent in 1983 to 8 per cent in 1990, but then rose to 10 per cent in 2000.((Redmond, Patulny and Whiteford (2013): ‘The Global Financial Crisis and Child Poverty: The Case of Australia 2006–10’ Social Policy & Administration, Vol. 47, No. 6, December 2013)) More recent research published by ACOSS and the Social Policy Research Centre (measured on a different basis, after deducting housing costs) found that child poverty rose from 15 per cent in 2004 to 17 per cent in 2014.((ACOSS (2016) Op.Cit.))

Poverty is harmful for children and affects their well-being, now and into the future.

Poverty is not just about numbers. Poverty has real impacts on children’s lives.

The Salvation Army’s (2017) survey of children in families states:

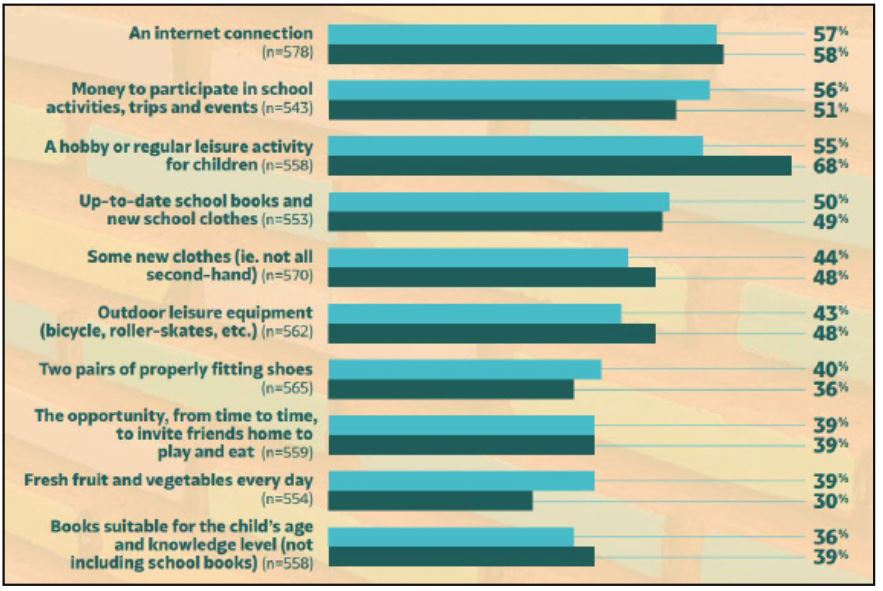

Our survey included a total of 1,495 children across 638 households; of these more than half (54%) experienced severe deprivation and went without five or more essential day-to-day items. The top 10 items that respondents could not afford for their children related to connectedness, education, social participation and basic nutrition. For households with children aged 17 or younger:

- Approximately one in five could not afford medical treatment or medicine prescribed by the doctor and nearly one in three could not afford a yearly dental check-up for their child

- Half could not afford up to date school items and 56% did not have the money to participate in school activities

- More than half (55%) could not afford a hobby or outside activities for their child

- Almost three in five respondents could not afford an internet connection for their child

- Nearly two in five could not afford fresh fruit or vegetables every day and nearly one in four could not afford three meals a day for their child.

Respondents reported that they experienced shame and guilt that their children had to go without and miss out, although there was little that they could do to change the situation.((Salvation Army (2017): The hard road, National Economic and Social Impact Survey p. 46))

The vast majority of families seeking emergency assistance (87%) received social security payments, including 38 per cent relying on Newstart Allowance and 19 per cent on Parenting Payment.

There were a number of items children did not have because their families could not afford them, including:

Children and young people deprived of food, clothes and other materials may reduce their engagement with school due to hunger, shame or being excluded or marginalised, impacting children’s development, educational, and eventually employment opportunities.((Redmond et al (2016) Op.Cit.))

Children of single parents are doing it tougher

In 2009, indexation of family payments to wage growth was removed, which reduced the value of these payments by an estimated $20 per fortnight. This would be hardest felt by very low-income families, particularly single parents.

The latest research from the Social Policy Research Centre at the University of NSW finds that single parents receiving Newstart Allowance are unable to afford a minimum and healthy standard of living. At $544 per week (including Newstart Allowance, Family Tax Benefits and Rent Assistance), their social security payments fall short of a minimum budget by $132 per week.((Peter Saunders, Megan Bedford (2017): Budget Standards: A new healthy living minimum income standard for low-paid and unemployed Australians, UNSW))

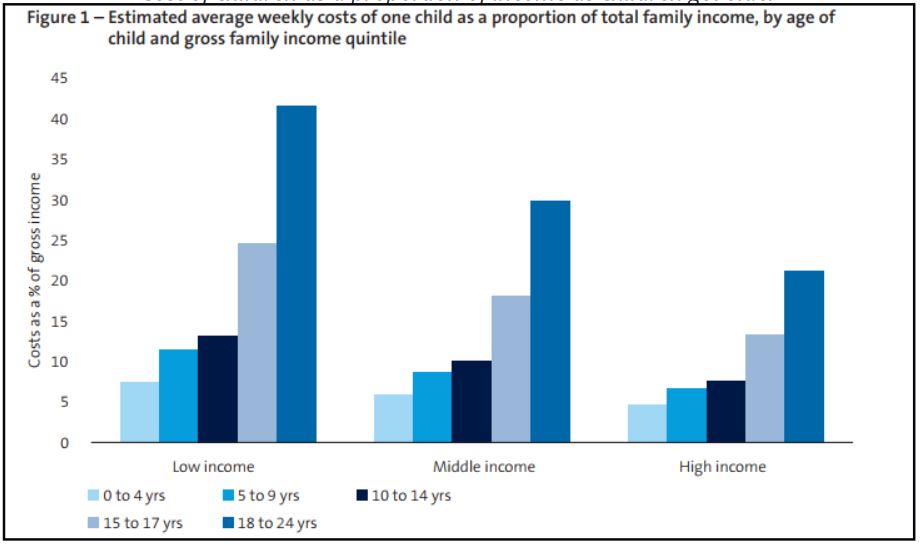

Absurdly, social security payments for single parents fall as their children grow older and become more expensive.

- When their youngest child turns five, Family Tax Benefits drop by $23 per week.

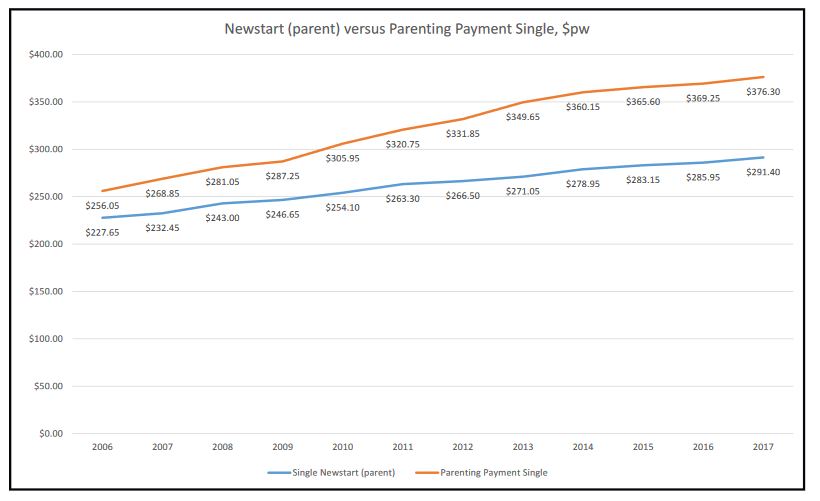

- When the child reaches eight years, the parent is moved from Parenting Payment to the lower Newstart Allowance, cutting the family’s income by another $85 a week.

In 2016, 600,000 children under 16 years (one in eight or 13 per cent) were in families without paid work, including 6 per cent of children in couple families and 45 per cent in single parent families.((Australian Bureau of Statistics (2016): Labour force status of families))

Again in 2016, the unemployment rate among single parents was 14 per cent, more than twice the national unemployment rate (6%). This reflects the challenges faced by single parents to find child care, retrain, and then find a job that is family-friendly.

Unemployment is too high and social security payments are too low.

Australia is not providing enough jobs for those who need them. There is only one job available for every 10 people who are out of paid employment, or want more paid work.

More than 500,000 people are looking for full-time work, and more than 225,000 are looking for part-time work.((Australian Bureau of Statistics (2017): Labour force, Australia, August 2017)) Overall, 5.6% of the workforce is unemployed and another 8.7% is under-employed; that is, unable to get the extra working hours they need.((Australian Bureau of Statistics (2017): Ibid))

Unemployed parents receive too little help from ’jobactive’ employment services. Many parents returning to the paid workforce need career advice and training to update their skills to give them a chance of finding a job. Most do not receive this.

Many parents lacking paid employment will find that child care is less affordable due to a government decision to restrict their child care subsidies to a maximum of 12 hours a week, down from 24 hours.((Doyle, J. (2017): ‘Government defends childcare package as sector says it’s been let down’ ))

In 2014, 52 per cent of people in families receiving Parenting Payment lived below the poverty line, along with 60 per cent of people in households relying on Newstart Allowance.((ACOSS Poverty Report (2016), poverty line set at 50% of median household income))

If families with children have to rely fully on social security payments, especially the meagre Newstart Allowance, they are very likely to be living below the poverty line.

Unsurprisingly, low-income families spend a far greater proportion of their income on children, which increasing to almost 45 per cent as children reach 18.

When we look at the key components of financial assistance currently going to low income families, we can identify a number of problems:

- The base rate of the primary working age payment, Newstart Allowance, is too low for both people with and without children to provide an adequate standard of living.

- Indexation of working age and family payments to price movements alone means that payment rates are falling faster behind community living standards.

- Family payments trend downwards as children get older, failing to reflect the cost of children.

Anti-poverty payments continue to be cut.

Since 2006, social security payments that play a crucial role in preventing child poverty have been repeatedly cut.

- In 2006, single parents were denied Parenting Payment Single (PPS) if their youngest child was eight years or more, and they had to apply for Newstart Allowance which was $29 per week less. People already receiving Parenting Payment Single were allowed to continue to receive it until their youngest child reached 16 years.

- From 2009, the higher rate of Family Tax Benefit for families at risk of poverty has been frozen in real terms (increasing in line with the CPI but not wages, as was the case before that).

- In 2013 this rule was changed, and 80,000 single parents receiving Parenting Payment Single were moved onto Newstart Allowance, cutting their income by $85 per week.

- In 2017, Family Tax Benefit rates were frozen in absolute terms (not even indexed to inflation) for two years.

Current legislation before the parliament would cut benefits further, including:

- Cutting payments to single parents undertaking study or training;((ACOSS (2017): Submission on Social Services Legislation Amendment (Better Targeting Student Payments) Bill 2017 Community Affairs Committee))

- Extending the waiting period for people with modest assets when they claim income support payments, including families;((ACOSS (2017): Submission on Social Services Legislation Amendment (Payment Integrity) Bill 2017, Community Affairs Committee)) and

- Reducing the amount of the first payment income support claimants receive, including people experiencing a separation, poor health or a housing crisis.((ACOSS (2017): Submission on the Social Services Legislation Amendment (Welfare Reform) Bill Community Affairs Committee))

We call on government to take swift and determined action to reduce child poverty in Australia.

Australia’s child poverty trend is heading in the wrong direction. We can, and must, reverse the tide.

Thirty years ago the Federal government reduced child poverty by 30 per cent. The evidence is there. It can be done.